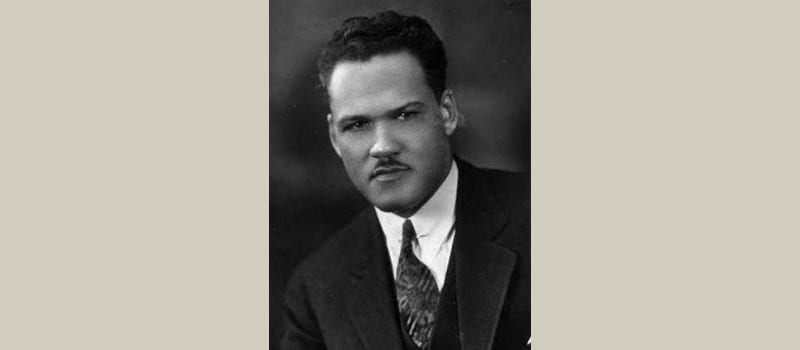

Frederick Douglass Patterson, 1901-1988

Two extraordinary activists of their respective times resided within three blocks of each other in the Anacostia section of the District of Columbia. Frederick Douglass, the great 19th century social reformer and human rights advocate, last lived in the Cedar Hill neighborhood. Frederick Douglass Patterson, a namesake to the former slave, was born in the Buena Vista Heights neighborhood on Oct. 10, 1901. Not only did Frederick Douglass Patterson share the statesman’s name, but he was also similarly imbued with a gift for launching sweeping societal advancements.

Like Douglass, the young Patterson overcame great odds and inspired others to do the same. Orphaned at 2, Patterson was reared by various family members from Washington, DC, to Texas. Although the siblings, aunts and uncles who cared for the young Patterson did so with the best intentions, the youngster was understandably affected by the death of his parents and his transient housing arrangements. As late as the eighth grade, his classmates voted him least likely to succeed.

When his sister, Bessie, took the young boy under her wing, she made great sacrifices to assure him a good education. She enrolled him in the elementary school of Samuel Huston College (now Huston-Tillotson College) in Austin, TX, for which she paid $8 a month out of her $20 salary. Her investment paid off. The boy’s passions for education were sparked during his years at Prairie View Normal and Industrial Institute (now Prairie View A&M University) when he was assigned to the Agriculture Department and began interacting with a number of top veterinarians. Dr. Edward B. Evans served as a particular inspiration to the boy, who would follow in his role model’s educational path and attend Iowa State College.

“I learned a lesson with regard to race that I never forgot: how people feel about you reflects the way you permit yourself to be treated. If you permit yourself to be treated differently, you are condemned to an unequal relationship.”— Frederick D. Patterson

As a college student, the young man flourished. Patterson would receive three advanced degrees over the next nine years. By age 31, he had achieved a doctorate of veterinary medicine and a master of science from Iowa State, and a doctorate of philosophy from Cornell University. He then returned to Tuskegee Institute (now University), where he had already spent a short time teaching, as head of its Department of Agriculture and the first person on the faculty to earn the doctorate. Under his tenure, the veterinary program reached such outstanding quality that the state of Alabama granted funds for white students to study veterinary science there, a unique occurrence in the segregated South.

Dr. Patterson’s rise to academic stardom was not without its challenges. His career was infused with the juxtaposition between eloquent academic lessons and stark racial ones. Although he was the only African American in Iowa State’s veterinary program, the integrated campus would provide him with a relatively unfettered experience. However, he had to endure a humiliating situation at a summer military camp. Because he and one other African American student ate at a separate table from the white students, he was treated as a “pariah,” he wrote in his autobiography: “I learned a lesson with regard to race that I never forgot: how people feel about you reflects the way you permit yourself to be treated. If you permit yourself to be treated differently, you are condemned to an unequal relationship.”

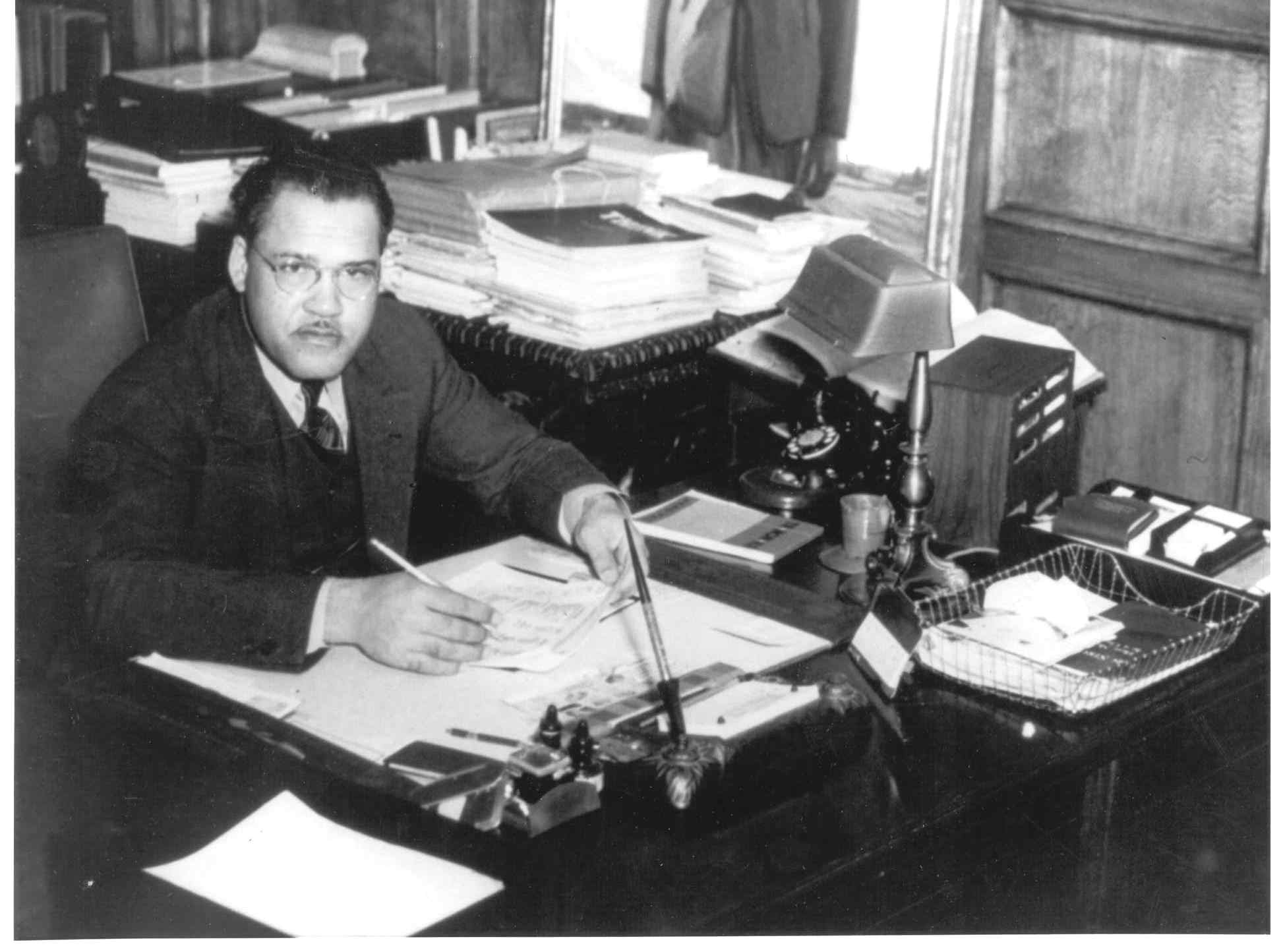

Leading Tuskegee

His range of experiences endowed Dr. Patterson with the wisdom and vision that inspired a committee to select the young man as the third president of Tuskegee Institute in 1935. At the age of 33, he was conscious enough about his youthful rise to the presidency that he told the selection committee that he was 34 years old, since he was technically into his 34th year. Tuskegee would remain in his blood in more ways than one. That same year, Dr. Patterson married Catherine E. Moton, the daughter of Robert Russa Moton, the second president of Tuskegee Institute. His Tuskegee presidency would last nearly a quarter of a century, until 1953; his marriage, until his death in 1988.

During his tenure at Tuskegee, Dr. Patterson transformed the baccalaureate institution into a prestigious university with cutting-edge graduate programs, all of which are flourishing today. He founded the commercial dietetics program, which infused professional cooking with business and service savvy and placed African American students in unprecedented high-level internships across the country. The veterinarian understandably took personal interest in the school’s veterinary medicine program, which afforded southern African Americans the only opportunity to become veterinarians in that region of the country. Tuskegee has graduated 75 percent of the nation’s African American veterinarians. His foresight into emerging fields also prompted him to spearhead the engineering program, which from its inception enabled African Americans to gain high level technical jobs across the country. He became so engaged in the commercial aviation program he initiated that he learned to fly.

“The more conservative element of Negroes differ from those who hold the most radical views in opposition to segregation only in terms of time and technique of its elimination. All Negroes must condemn any form of segregation based on race, creed or color.”— Frederick D. Patterson

The Beginning of the Airmen

His contributions to aviation did not end there. In the late 1930s, Dr. Patterson defied all of the political, social and financial odds against training African American youth to fly military airplanes. Not only did he win for Tuskegee a coveted federal contract to establish a training site, but he persuaded the government to establish a full air base at Tuskegee. That accomplishment gave birth to the now legendary Tuskegee Airmen of the World War II U.S. Army Corps. Nearly 1,000 African Americans completed their first training at Tuskegee Army Air Field. Half went overseas during World War II as combat pilots, and despite segregation’s obstacles, the Tuskegee Airmen boasted a spotless record—not one bomber was lost to enemy planes in 1,500 missions. This feat contributed significantly to the eventual desegregation of the American armed forces.

As a college president, Dr. Patterson had an impact on the community that extended to those at all levels of the educational spectrum. As he surveyed the town of Tuskegee, the vast numbers of residents whose wooden houses were inadequate and frequently destroyed by fire struck him. Realizing the capacity of his largely vocational college, he pooled available talent and resources and created an intricate program that trained and assisted the low-income citizens in building new, sound homes made of a unique concrete construction. Methods associated with the “Tuskegee concrete block” were recognized by the federal government as a pragmatic approach to low-income housing and were adapted as models for rural homes, both domestically and internationally.

The United Negro College Fund—An American First

As Dr. Patterson continued to reach out to more expansive constituencies, his most far-reaching initiative took flight in 1944. While searching for new methods by which private black colleges could become more financially sound, he conceived and founded the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), the first cooperative fundraising venture in American higher education. In 1964, he was elected president and chief executive officer and served in both capacities until 1966. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., took immediate interest and an active role in the burgeoning organization; extraordinary leadership has propelled the organization to record heights ever since.

Dr. Patterson’s prominence in higher education won him an invitation to sit on President Harry S. Truman’s President Commission in 1946-1947. That group’s findings influenced every major piece of higher education legislation during the 1960s. Among the historic developments that evolved from the commission were the system of community colleges and the enactment of Title III of the Higher Education Act of 1965, which brought direct institutional support to America’s smaller colleges and universities. Both policies continue to affect American higher education on a widespread scale.

As his educational and philanthropic interest continued to merge, Dr. Patterson was appointed a director at the Phelps-Stokes Fund, a philanthropic foundation primarily concerned with the education of African Americans. He served as director from 1953 to 1958. He then served as president from 1958 to 1969. There, he concerned himself with the education of African Americans, Native Americans, Africans and disadvantaged white youth. During his tenure, he advanced Phelps-Stokes in its primary goals, which remain intact. The organization continues to sponsor research studies, administer scholarship and fellowship programs, conduct professional development programs and engage in public education programs. During his years at both the Phelps-Stokes Fund and the Robert R. Moton Memorial Institute, Dr. Patterson remained closely tied to the institutions he championed. He served on the boards of a number of HBCUs including Hampton Institute (now University), Tuskegee Institute (now University), Interdenominational Theological Center and Bennett College. He also served as the chairman of Bennett’s Board of Trustees. Additionally, 19 colleges and universities awarded Dr. Patterson 20 honorary degrees.

The Legacy Endures

Of all his endeavors, Dr. Patterson’s starkest accomplishment remains the scope of the people he influenced. Over the course of his 87 years, he inspired Americans as well as African Americans. He influenced higher education policy and practice. He changed the way that philanthropy would be conducted. He generated a dynamic that pushed every organization he touched to its limit. Hundreds of thousands of Americans continue to feel the effects of Frederick D. Patterson’s work and dedication.

Less than one year before his death, he received his highest honor. On June 23, 1987, President Ronald Reagan awarded Dr. Patterson the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Its inscription reads, “By his inspiring example of personal excellence and unselfish dedication, he has taught the nation that, in this land of freedom, no mind should go to waste…”.